Search

The Ugly Stepsister: When desire is 'afoot'!

- Maria Isabel Nieves Bosch

- Jun 9, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Jul 9, 2025

Warning: SPOILERS AHEAD!

This 2025 Norwegian adaptation, set in the mid 1800s, finally delivers what the original story of Cinderella depicts: the ugly stepsister's desperate attempt of self-mutilation to marry the prince. Yet, no matter how much she tries or how much pain, cruelty, and humiliation she suffers, the protagonist's sweet, pretty, and pink fantasy clashes with reality. With much attention to detail, the writer and director, Emilie Blichfeldt, plants Agnes (the character of Cinderella) as Elvira's (the ugly stepsister) counterpart or foil instead of the villain. This is a layered adaptation where the protagonist Elvira, played outstandingly by actress Lea Myren, ignites both pity and disgust for the lengths she goes to when making her dream come true. The colors help outline the development of each character and the juxtaposition between Elvira and Agnes. With the collaboration of cinematographer Marcel Zyskind, the film captures with visual impact the tone of the original fairytale since there's beauty, compassion, and white doves as well as cruelty, violence, and all types of disgusting worms. The film weaves these elements harmoniously, keeping the viewer's attention glued to the screen even when an eye gets violated with a needle.

The film starts when Rebekka (the stepmother) and her two daughters, Elvira and Alma, journey to the new house where Agnes lives with her father. When the three women get on the coach, a man offers his hand for each lady: Alma dismisses the man's hand and even scorns it; Rebekka smiles and politely accepts the man's hand; lastly, Elvira, completely charmed by the man's gesture, smiles and curtsies before stepping onto the carriage. This brief and seemingly simple scene offers information to the viewers about the role each of these characters play in their environment dominated by patriarchal standards, and presents the quality with which the film unfolds.

Blichfeldt creates a space to scrutinize these women and their choices while the ultimate symbol of the patriarchy rots in his own house.

This Cinderella adaptation by Blichfeldt creates a space to scrutinize these women and their choices while the ultimate symbol of the patriarchy (father/husband) rots in his own house. Once Rebekka marries the head of the household, they dine together as a family just once before he abruptly dies. Interestingly, before his death and to his own amusement, he throws cake at Elvira's face (whose naiveté makes her laugh along) and then, when dying, uncontrollably coughs blood at his own daughter's face who screams in terror. This scene can potentially be read as one character not recognizing the villain nor her own submission (in this case Elvira laughing along) and the other character knowing the villain is also her closest ally. Nonetheless, his death brings forth the matter of finding a new benefactor, which Rebekka points out is not easy for, "a widow with saggy tits and two hopeless daughters."

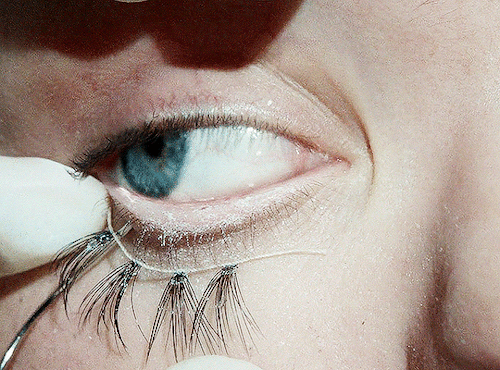

Body horror brings forth the gruesome element of the original fairytale with the intention to increase irony when destroying one's body to meet beauty standards (similar to the 2024 movie, The Substance). While the father's decaying corpse remains on a table throughout the film, maggots and worms feast on his flesh, much like the tapeworm consuming Elvira's body. In pursuit of having a desired body, she chooses to swallow a worm egg and let the worm hatch inside her stomach so that it eats everything she eats. Of course, it also becomes a detriment when she starts losing chunks of hair and has bald spots on her head. Moreover, the body horror truly manifests with the surgical procedures Elvira undergoes to have the perfect nose and lush eyelashes. Rebekka seeks the services of Dr. Esthetique who breaks her daughter's nose, sniffs cocaine, and proceeds to sew long eyelashes into Elvira's eyeline. The latter feels reminiscent of Dalí and Buñuel's Un Chien Andaluz (1929), with the close-up of a woman's eye getting sliced. All these procedures lead to the most gruesome, gory and brutal self-afflicted body modification regarding her toes.

The female body in this movie functions to highlight the contested psychological manipulation of what it means to be a woman

In traditional horror films, such as Rosemary's Baby (1968), Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) and Bram Stoker's Dracula (1992), Linda Williams argues "...the bodies of women figured on the screen have functioned traditionally as the primary embodiments of pleasure, fear, and pain." (Williams, "Film Bodies..." in Film Theory & Criticism, p.605) However, in The Ugly Stepsister, Elvira's body only knows pain either afflicted by others (nose job, fake eyelashes) or afflicted by herself (swallowing worm egg, cutting off toes). The female body in this movie functions to highlight the contested psychological manipulation of what it means to be a woman. In Agnes' case, she's already born beautiful and finds love with Isak (the stable boy) but attains pleasure before being punished and forced to work as a servant. Agnes also becomes a victim of unwanted male attention and sexual harassment while Elvira watches without understanding Agnes' struggle for body autonomy. When a merchant arrives to deliver a dress for Elvira to wear at the ball, he forces a violent kiss on Agnes, who pushes him off and spits on the floor. In contrast, when the man touches Elvira to accommodate her breasts in the gown, she remains completely passive.

In other words, Elvira never internalizes the objectification of the female body in her own violent pursuit to embody male pleasure. Rebekka, nonetheless, knows the gender dynamics and uses her own body to make transactions, even to that same perverted man who essentially assaulted the younger women moments before. Although cruel and unempathetic to Elvira, Rebekka does not play the villain. Her culminating image places her enveloped in darkness, wearing red lingerie in bed with a rich young man, feeling ashamed and burdened. She no longer has the youth or body that in the past allowed her power. In a way, her demise rests on reinforcing the patriarchal norms instead of evolving or resorting to other ways even for her daughter's sake.

Comments